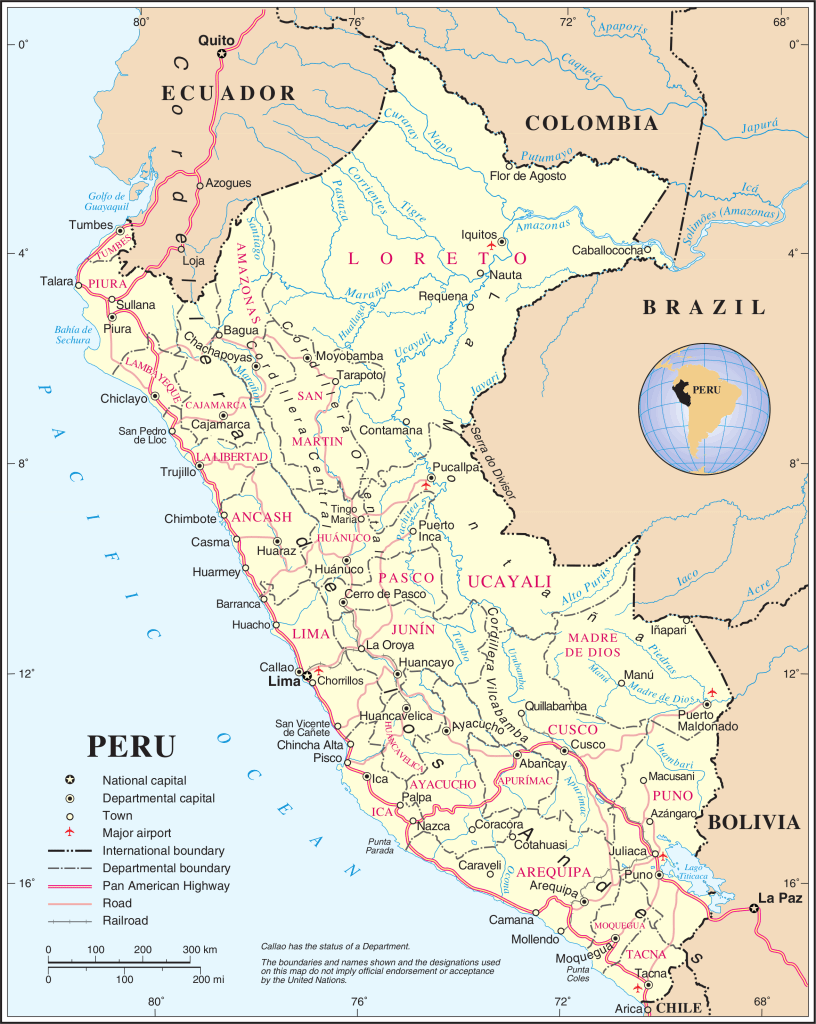

Peru is located in the Western Coast of South America. It is entirely situated in the Southern Hemisphere and faces the Pacific Ocean on the west. Peru is bordered by Ecuador and Colombia to the north, Brazil to the east (the longest border, Bolivia to the Southeast and Chile to the south.

According to official international databases, including the CIA World Factbook and the World Bank, Peru covers a total area of approximately 496,225 square miles (1,285,216 km2). This is further divided into a landmass of 494,209 square miles (1,279,996 km2) and internal water surfaces, such as rivers and lakes, totaling 2,015 square miles (5,220 km2).

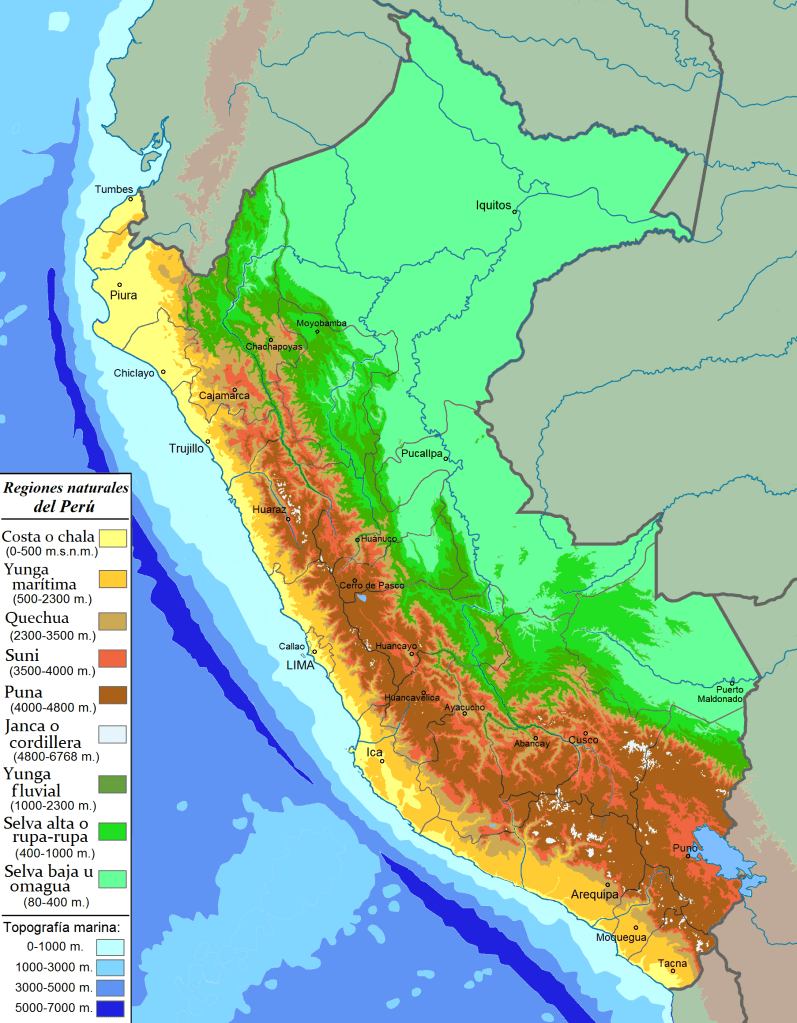

Peru’s Geographical Regions

Peru has eight geographical regions as proposed by Javier Pulgar Vidal. They are:

- La Chala or coast

- La Yunga

- Quechua

- Suni or Jaica

- La Puna

- La Janca

- La Rupa Rupa or High Jungle

- Omagua or Low Jungle ( or Amazon.)

I will cover the first four areas in this page, and continue the rest in a separate one so it is not so overwhelming.

This is a map showing the regions:

1. La Chala

The Chala, or Coast, is the first of Peru’s eight natural regions, stretching from the Pacific shoreline up to an elevation of 500 meters. This narrow, arid strip is defined by a unique climate where the cold Humboldt Current creates a persistent sea mist called garúa. This mist prevents rain but provides enough moisture to support “fog gardens” known as Lomas on the hillsides. In these seasonal ecosystems, the yellow Amancaes flower, wild tomatoes, and tara trees flourish despite the surrounding desert.

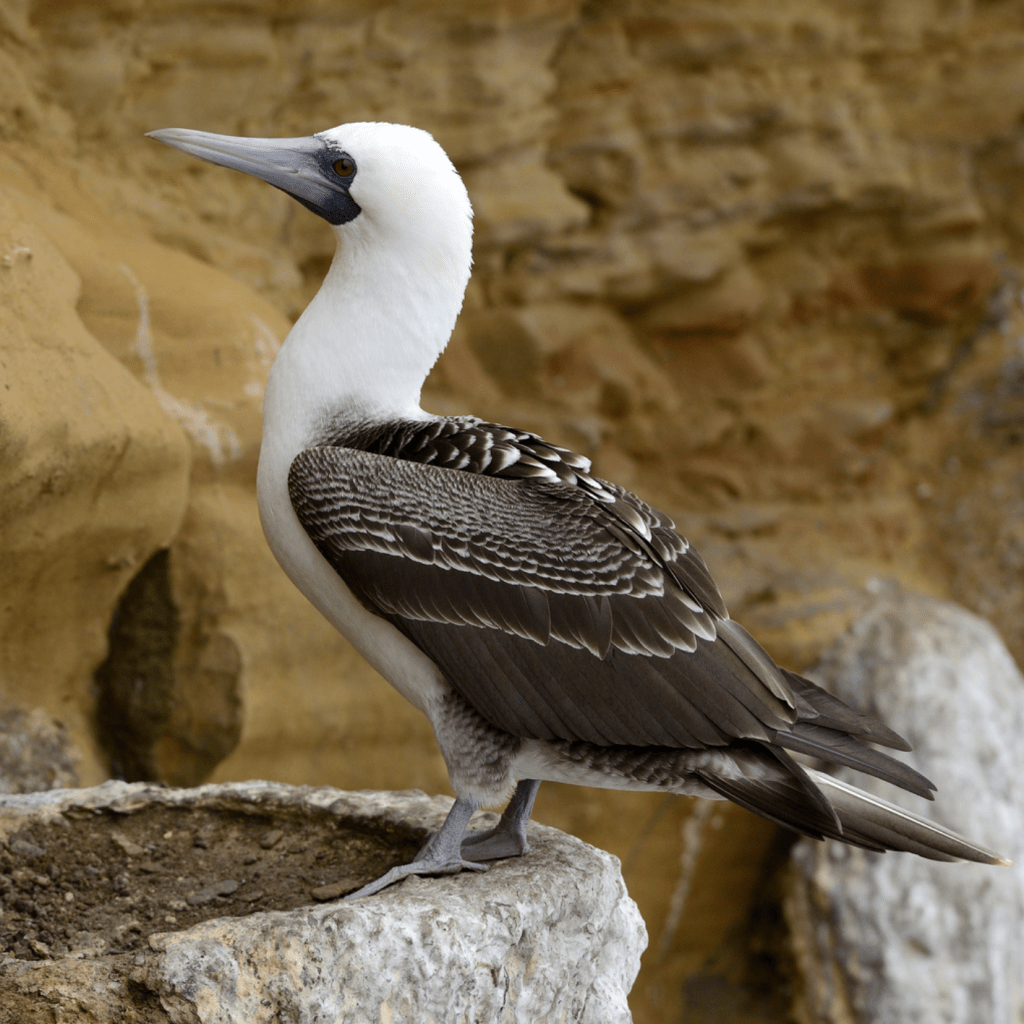

Along the river valleys that cut through the sands, the landscape turns green with carob trees, reeds, and wild canes. In the far north, where the water is warmer, dense mangrove forests provide a unique habitat for coastal life. The region is also a biological powerhouse due to its nutrient-rich waters, which support massive populations of anchovies, sea lions, and guano-producing seabirds like the piquero.

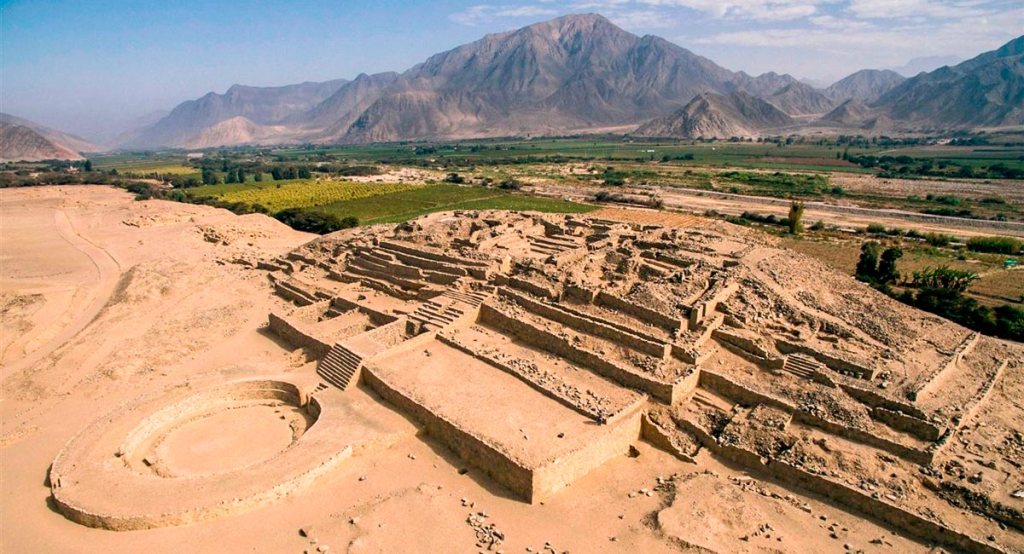

Historically and economically, the Chala is the heart of Peru. It was home to ancient civilizations like Caral and remains the most densely populated region today, hosting major urban centers like Lima. Life here is a constant balance between the barren desert and the incredible wealth of the sea and river oases.

Lima

Lima, the capital of Peru, was founded by the Spanish conquistador Francisco Pizarro on January 18, 1535. Originally named La Ciudad de los Reyes (The City of Kings) to honor the feast of the Epiphany, the city’s official name eventually shifted to Lima, a Spanish variation of the indigenous Quechua word Rímac, which means “talking river.” Established in the Rímac River valley of the Chala region to provide a strategic coastal gateway for trade, this sprawling desert metropolis now serves as Peru’s political and economic heart. Today, it blends a deep colonial history and ancient adobe pyramids with a modern reputation as a global gastronomic capital, housing nearly a third of the country’s population beneath its famous coastal mist.

HERE is a beautiful 360 view as well.

2. La Yunga

The Yunga region is a diverse and fertile transitional zone situated between the coastal Chala and the high Andean Quechua, serving as a primary agricultural hub for Peru. It is divided into two distinct zones: the Maritime Yunga on the western slopes (500 to 2,300 meters), which experiences a dry, desert-like climate, and the Fluvial Yunga on the eastern slopes (1,000 to 2,300 meters), characterized by a warmer, subtropical climate with seasonal rains. This region is famous for its narrow ravines and “talking rivers” that create deep, picturesque canyons. Because of its steady temperatures and sunny days, the Yunga is often called the “Land of Perpetual Spring,” providing the perfect environment for cultivating high-value fruits like lúcumo, cherimoya, guava, avocado, and citrus, alongside industrial crops like sugar cane.

These are photos of the Fluvial Yunga from the San Pedro de Chonta Regional Conservation Area (RCA) was officially established in Peru’s Huánuco department, spanning 128,220 acres (51,889 hectares) in August 2025. These photos are from the andesamazonfund.org:

There is an estimated 200 species of orchids that live in the Yunga area.

And these are some of the fruits mentioned:

Lucuma:

Cherimoya:

Guava

In the next two photos is the Cinchona tree. It is the National Tree of Peru and it is featured in its National Emblem. The bark has been used for medicinal purposes for centuries, most notably for treating Malaria.

The vegetation in this region is rugged and well-adapted to steep terrain, featuring the molle (pepper tree), white agave, and cacti such as pitahaya and chuná. This landscape also supports a variety of birdlife, most notably the chaucato (long-tailed mockingbird) and the taurigaray. The Andean Cock of the Rock is also endemic to this area. While the Maritime Yunga is known for being a sun-drenched escape from the coastal mist of Lima, it is also prone to huaicos (seasonal mudslides) due to its steep, rocky geography and sudden mountain rains. Despite these challenges, the Yunga remains one of Peru’s most productive and scenic regions, bridging the gap between the arid coast and the towering peaks of the Andes.

I am overwhelmed with how many birds, fruits and plants grow here! And before I move to the next region I wanted to point out that the famous site of Machu Picchu. Gemini said sits at an altitude of approximately 2,430 meters—which technically places it within the elevation range of the Quechua region (2,300–3,500m)—it is actually classified as being in the Fluvial Yunga or the “Ceja de Selva” (Jungle’s Eyebrow). This is because the site is located on the eastern slope of the Andes, where the dry, temperate climate of the Quechua gives way to a lush, humid cloud forest ecosystem. Even though it is lower in altitude than the city of Cusco (which is squarely in the Quechua region), Machu Picchu’s environment is defined by dense subtropical vegetation, high humidity, and frequent mist, which are hallmarks of the Yunga rather than the drier Quechua valleys.

Shall we go there? ¡Vamos!

3. Quechua

The Quechua region, situated between 2,300 and 3,500 meters above sea level, is often described as the most hospitable and “human” of the Andean zones due to its exceptionally mild, temperate climate. Spanning both the eastern and western slopes of the Andes, the landscape is a rhythmic alternation of fertile valleys and narrow watersheds that feed into common basins. This region is famous for its clear blue skies and “eternal spring” atmosphere, though it receives limited but vital summer rains that sustain its traditional agriculture. The flora is diverse and resilient, featuring the alder (aliso), the lambrán (or rambash), and the gongapa shrub, while the iconic gray thrush, known locally as the chihuanco, is the most characteristic bird of the region, often seen flitting through the valley orchards.

Because of its favorable climate, the Quechua region has been the agricultural heartland of the Andes for millennia, serving as the primary center for the domestication of many essential crops. It is the premier land for growing maize(corn) in countless varieties, alongside squash, passion fruit, papaya, wheat, and peaches.

And in this region one also finds the “improved potatoes”, the brown and yellow potatoes that are consumed all over the world.

Aside from potatoes, the Quechua region is also home to unique Andean tubers and root vegetables like the arracacha, which thrives in the rich, well-drained soil of the mountain slopes. Historically, this zone was so vital to the Inca Empire that many of their most important cities and “andenes” (agricultural terraces) were constructed here. Today, it remains the most densely populated area of the Peruvian highlands, hosting historic cities like Cusco, Cajamarca, and Arequipa.

Did you catch “andenes” … I immediately thought that The Andes mountains were named after the terraces by the Spanish as the word Andén means platform. But there is another theory that predates the Spanish, and it is that there were people that lived in the area called “Antis”… so who knows?

Before leaving this geographical region, I wanted to highlight an animal that is very important to the Andean culture: the cuy or Guinea Pig. Gemini said

The cuy, or guinea pig, is a small rodent native to the Peruvian Andes that has been a cornerstone of highland culture for over 5,000 years. Unlike in many Western countries where they are seen as pets, the cuy was domesticated by ancient Andean civilizations as a primary source of high-protein, low-fat meat. They are perfectly suited for the rugged mountain lifestyle, living freely in traditional kitchens across the Quechua and Suni regions to stay warm near stone hearths while feeding on alfalfa and vegetable scraps.

Beyond its role as a staple food, this native animal holds deep symbolic and medicinal significance in Andean society. Traditional healers use the cuy in rituals to diagnose spiritual or physical ailments, believing the animal’s body can absorb a patient’s illness. Culturally, the cuy is so central to Peruvian identity that it is even featured as the main dish in the famous Last Supper painting in the Cusco Cathedral. Today, it remains a celebrated delicacy, often served crispy and whole during important festivals and community weddings.

Suni

The Suni region, also known as the Jalca, represents the rugged high-altitude transition zone of the Andes, situated between 3,500 and 4,000 meters above sea level. The terrain is markedly different from the temperate Quechua valleys below, characterized by steep, rocky slopes, narrow ravines, and a significantly colder, thinner atmosphere. While the area is still habitable, the climate is harsh and defined by frequent frosts that dictate what can survive in this “upper limit” of traditional agriculture. The landscape begins to trade the lush greenery of lower elevations for the rugged, golden tones of the high mountains, where the air is crisp and the sun is exceptionally intense during the day.

Despite the biting cold, the Suni is the true kingdom of the native potato, as many of the thousands of varieties found in Peru are specifically adapted to these frosty heights. The flora is headlined by the Cantuta, a vibrant bell-shaped flower known as the “Sacred Flower of the Incas,” and the hardy quinual tree, one of the few trees in the world capable of growing at such extreme altitudes. This region was historically strategic for the Inca Empire, serving as the perfect environment for producing chuño (freeze-dried potatoes) by utilizing the natural cycle of freezing nights and hot days. It remains a region of quiet, stark beauty, home to resilient birds like the zorzal negro and the allgay, marking the final gateway before entering the treeless, frozen heights of the Puna.

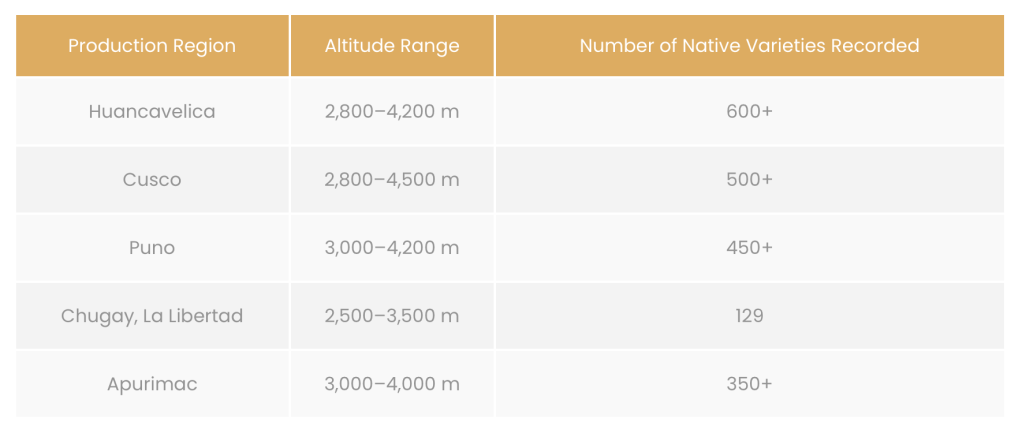

The potato originated in the high Andes of southern Peru and northwestern Bolivia. Genetic testing traces nearly all modern potato varieties back to a single origin point: the area surrounding Lake Titicaca. While the exact date is debated, indigenous communities began domesticating wild potato plants approximately 7,000 to 10,000 years ago, long before the rise of the Inca Empire.

The diversity found in Peru today is staggering as it is home to over 3,000 to 4,000 native varieties!!! These native potatoes come in every imaginable shape, size, and color—including deep purples, bright reds, and speckled oranges. They are adapted to thrive from the temperate Quechua valleys to the freezing, thin air of the Suni and Puna regions (above 3,500 meters).

Ready to see some of these potatoes?

This is the Cantuta flower, the national flower of Perú. It has been revered for many centuries for its cultural and spiritual significance.